Supervised learning: nonparametric regression

SURE 2025

Department of Statistics & Data Science

Carnegie Mellon University

Background

Recall: Model flexibility vs interpretability

- Generally speaking: trade-off between a model’s flexibility (i.e. how “wiggly” it is) and how interpretable it is

- Parametric methods (e.g. linear regression, GLMs): we make an assumption about the functional form, or shape, of \(f\) before observing the data

- Nonparametric methods: we do not make explicit assumptions about the functional form of \(f\) (i.e., \(f\) is estimated from the data)

- Parametric models are generally easier to interpret, whereas nonparametric models are more flexible

\(k\)-nearest neighbors (\(k\)-NN)

- Perhaps the simplest nonparametric method…

Find the \(k\) data points closest to an observation \(x\), use these to make predictions

- Need to use some measure of distance, e.g., Euclidean distance

Take the average value of the response over the \(k\) nearest neighbors

\(k\)-NN classification: most common class among the \(k\) nearest neighbors (“majority vote”)

\(k\)-NN regression: average of the values of \(k\) nearest neighbors

- The number of neighbors \(k\) is a tuning parameter (like \(\lambda\) is for ridge/lasso)

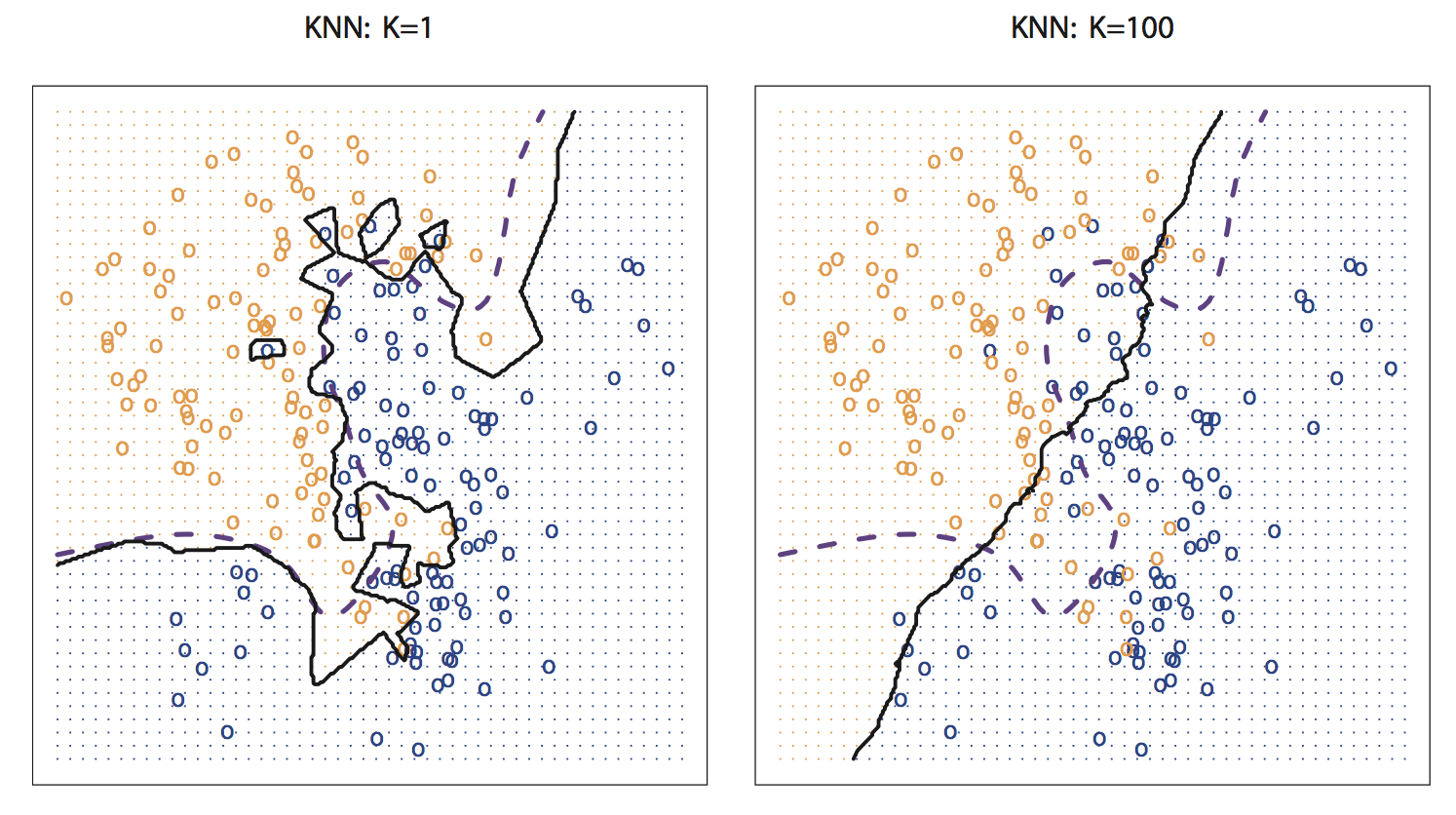

Finding the optimal number of neighbors \(k\)

Recall: bias-variance tradeoff

- If \(k\) is too small, the resulting model is too flexible: low bias, high variance

- If \(k\) is too large, the resulting model is not flexible enough: high bias, low variance

Moving beyond linearity

- The truth is (almost) never linear

- But often the linearity assumption is good enough

What if it’s not linear?

splines

local regression

generalized additive models

wavelets

- The above methods can offer a lot of flexibility, without losing the ease and interpretability of linear models

Generalized additive models (GAMs)

Resources

Book: Generalized Additive Models by Simon Wood

GAM resources GitHub repository

Generalized additive models (GAMs)

- Previously: generalized linear models (GLMs) (e.g., linear regression, logistic regression, Poisson regression)

- GLM generalizes linear regression to permit non-normal distributions and link functions of the mean \[g(\mathbb E[Y \mid X = x]) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \beta_2 x_2 + \dots + \beta_p x_p\]

What if we replace the linear predictor by additive smooth functions of the explanatory variables?

Entering generalized additive models (GAMs)

relax the restriction that the relationship must be a simple weighted sum

instead assume that the response can be modeled by a sum of arbitrary functions of each predictor

Generalized additive models (GAMs)

- Allows for flexible nonlinearities in several variables

- But retains the additive structure of linear models

\[g(\mathbb E[Y \mid X = x]) = \beta_0 + s_1(x_1) + s_2(x_2) + \dots + s_p(x_p)\]

- Like GLMs, a GAM specifies a link function \(g()\) and a probability distribution for the response \(Y\)

- \(s_j\) is some smooth function of predictor \(j\)

- GLM is the special case of GAM in which each \(s_j\) is a linear function

Why use smooth functions rather that just coefficients?

- Relationships between individual predictors and the response are smooth

- Estimate the smooth relationships simultaneously to predict the response by adding them up

- GAMs have the advantage over GLMs of greater flexibility (want to model the covariates flexibly, covariates and response not necessarily linearly related)

A disadvantage of GAMs/smoothing methods is the loss of interpretability

How do we interpret the effect of a predictor on the response?

How do we perform inferences for those effects?

Generalized additive models (GAMs)

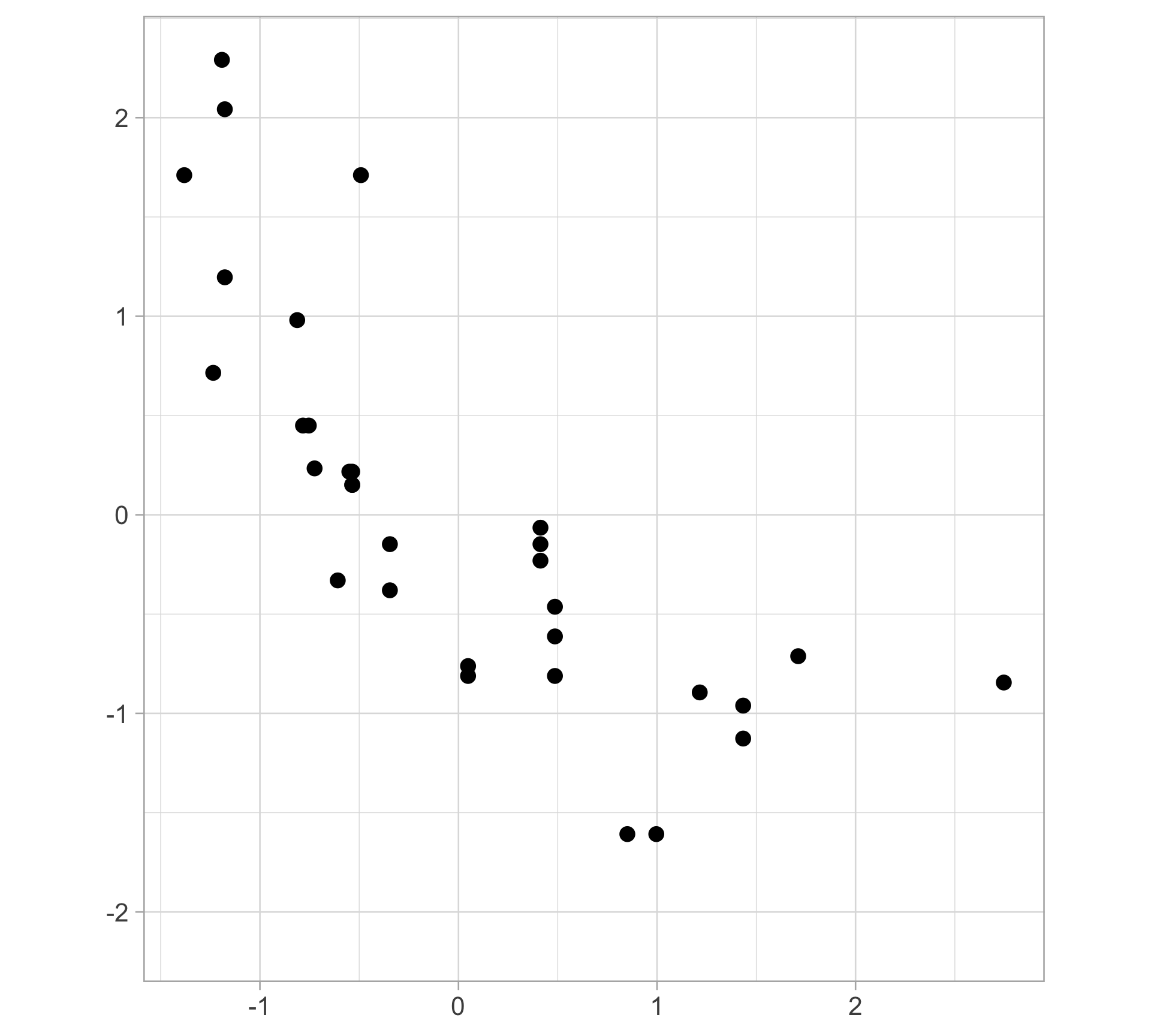

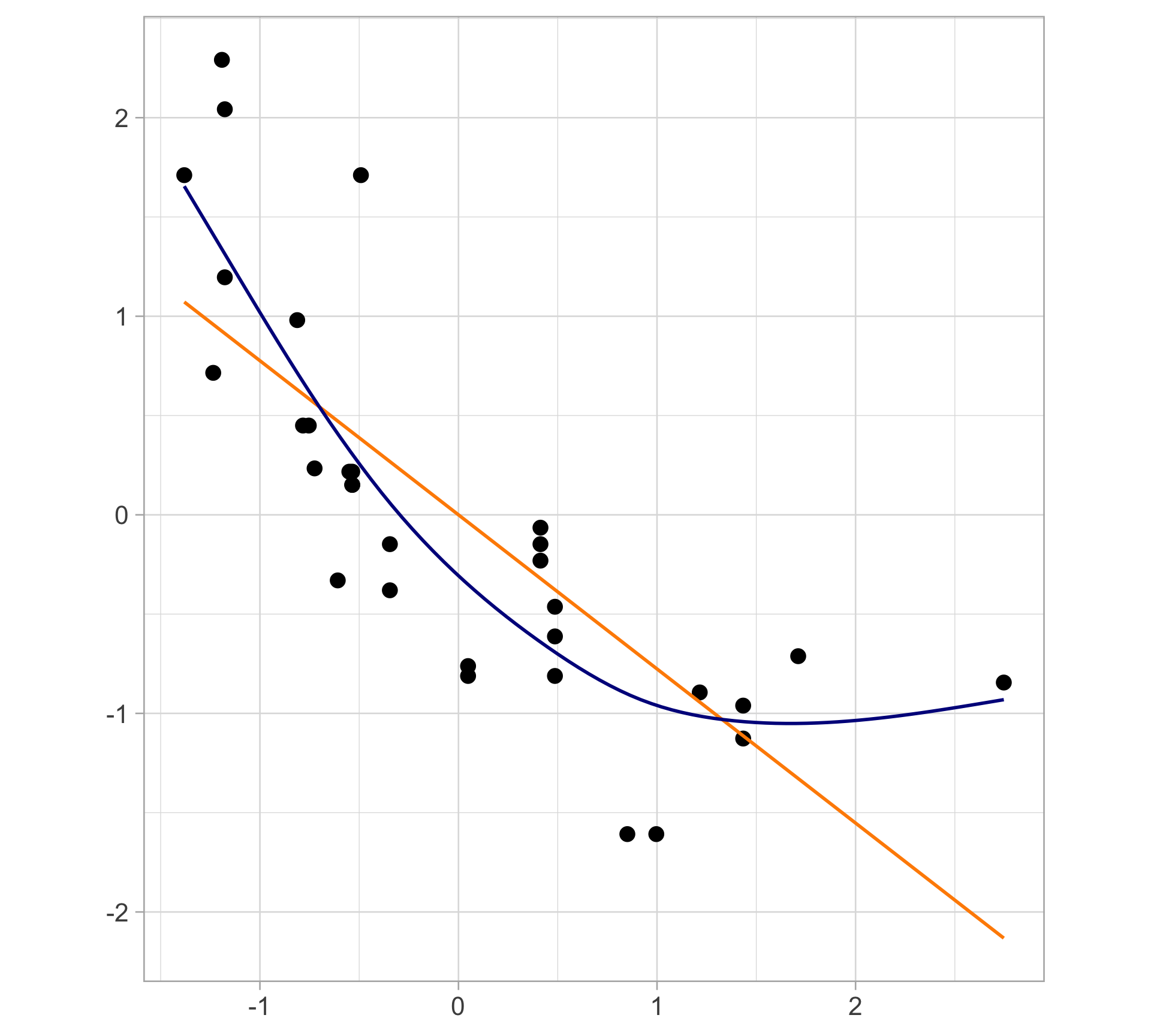

Toy example: is this linear?

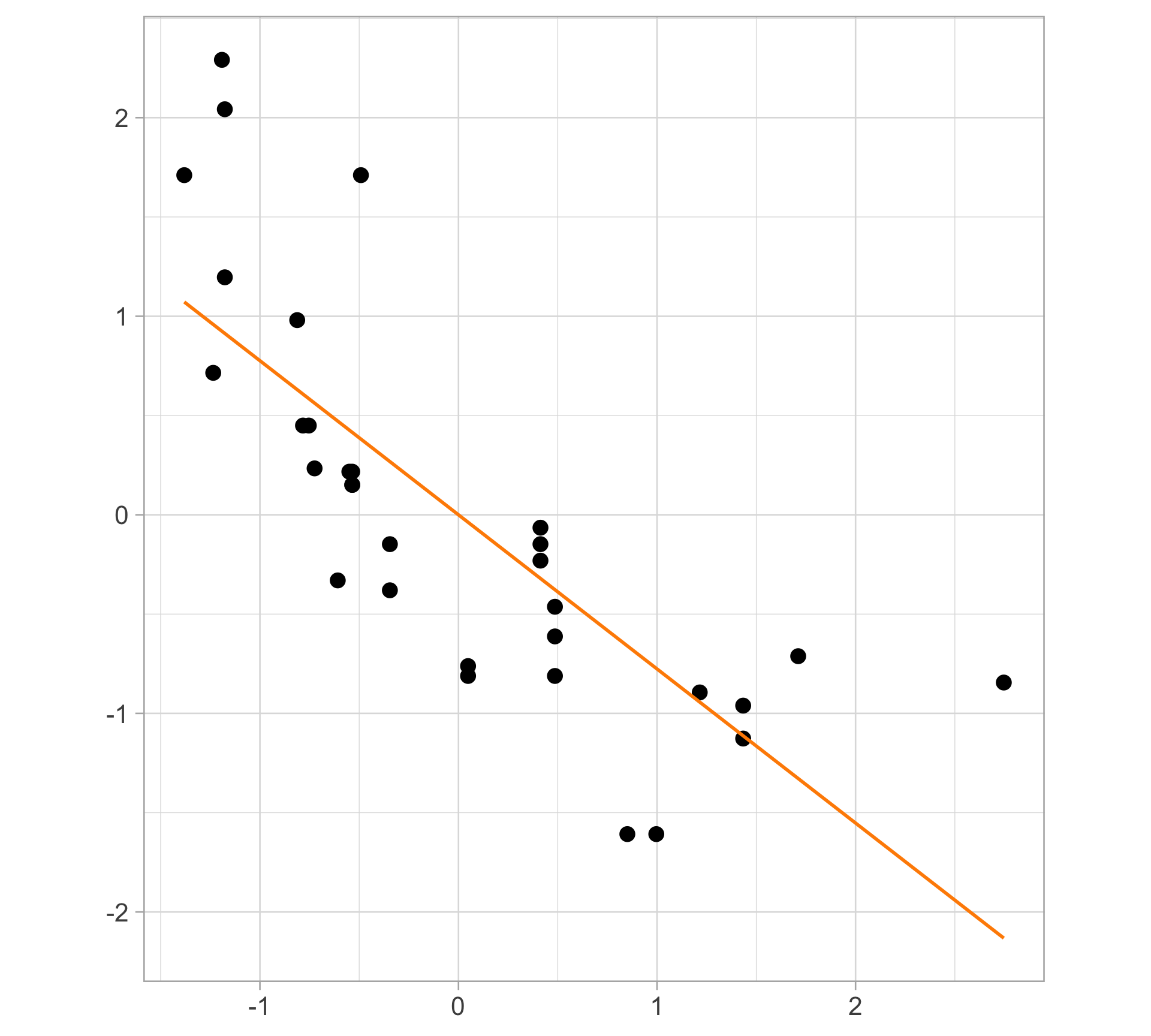

Toy example: linear regression fit

Toy example: GAM fit

Splines

- A common way to smooth and learn nonlinear functions is to use splines

- Splines can be used to approximate other, more complex functions

- Splines are functions that are constructed from simpler basis functions (usually polynomials), and the set of basis functions is a basis

- Each basis function \(b_k\) has coefficient \(\beta_k\). Spline is just the sum of the weighted basis functions

\[\displaystyle s(x) = \sum_{k=1}^K \beta_k b_k(x)\]

Weight basis functions to obtain spline

Why not just a polynomial fit?

\[y_i \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_i, \sigma^2)\] \[\mu_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i} + \beta_2 x^2_{1i} + \cdots + \beta_j x^j_{i}\]

In the polynomial models we use a polynomial basis expansion of \(x\)

- \(x^0 = 1\) (constant term), \(x, x^2, x^3, x^4, \dots\)

- We can keep on adding ever more powers of \(x\) to the model (hmm…)

- Runge phenomenon: oscillations at the edges of an interval—using higher-order polynomials doesn’t always improve accuracy

Smoothing splines

Use smooth function \(s(x)\) to predict \(y\), control smoothness directly by minimizing the spline objective function

\[\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - s(x_i))^2 + \lambda \int s''(x)^2dx\]

\[= \text{fit data} + \text{impose smoothness}\]

\[\longrightarrow \text{model fit} = \text{likelihood} - \lambda \cdot \text{wiggliness}\]

Smoothing splines

- The most commonly considered case: cubic smoothing splines

\[\text{minimize }\sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - s(x_i))^2 + \lambda \int s''(x)^2dx\]

- First term: RSS, tries to make \(s(x)\) fit the data at each \(x_i\)

Second term: roughness penalty, controls how wiggly \(s(x)\) is via tuning parameter \(\lambda \ge 0\)

Balances the accuracy of the fit and the flexibility of the function

The smaller \(\lambda\), the more wiggly the function

As \(\lambda \rightarrow \infty\), \(s(x)\) becomes linear

Smoothing splines

Goal: Estimate the smoothing spline \(\hat{s}(x)\) that balances the tradeoff between the model fit and wiggliness

Remember: Goldilocks principle

GAM recap

A framework to model flexible nonlinear relationships

Use little functions (basis functions) to make big functions (smooths)

The predictor matrix has columns for each basis function, evaluated at each observation

Use a penalty to trade off model fit and wiggliness

Need to make sure the smooths are wiggly enough

Examples

Predicting MLB HR probability

Data available via the

pybaseballlibrary inpythonStatcast data include pitch-level information, pulled from baseballsavant.com

Example data collected for the entire month of May 2024

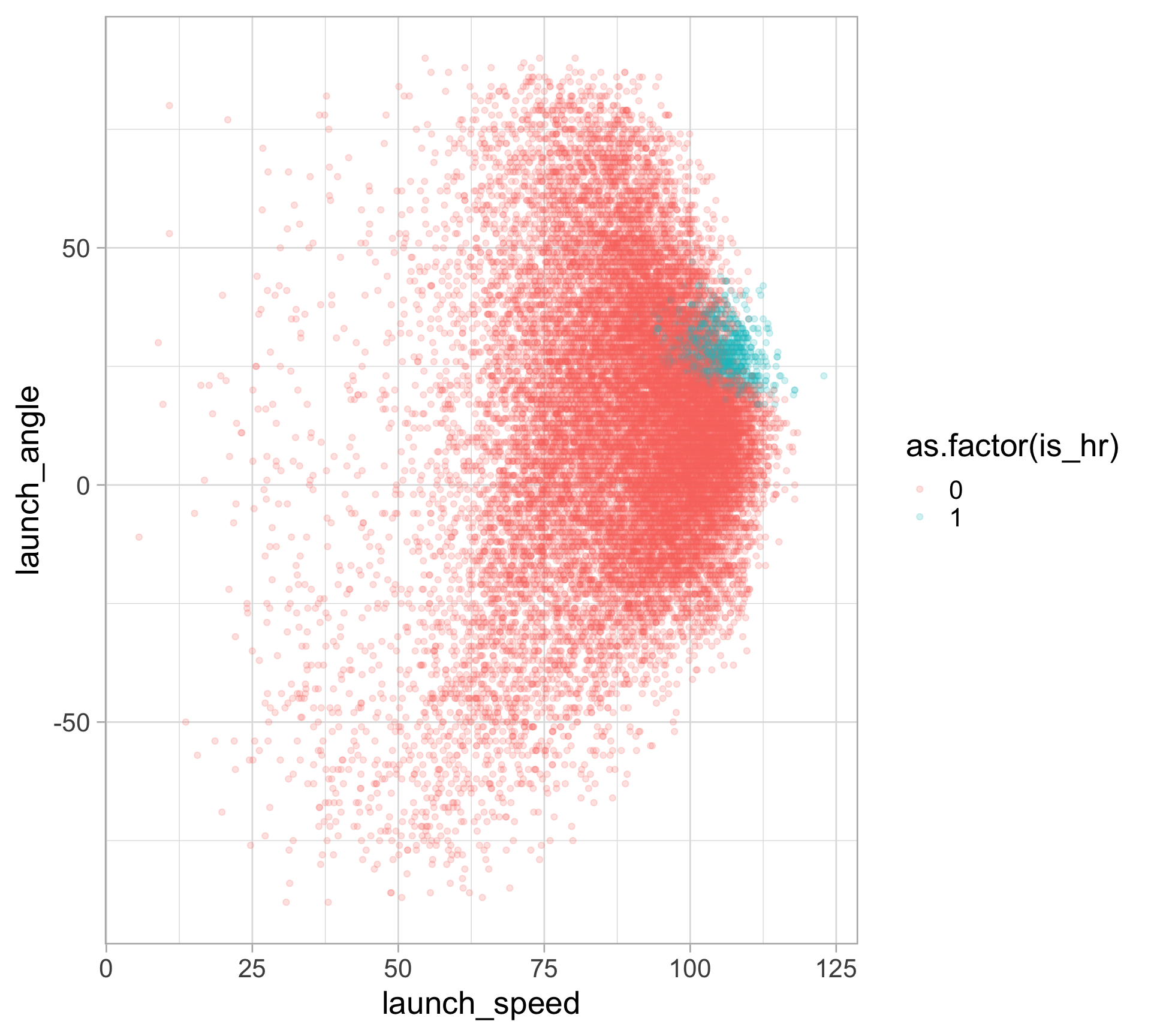

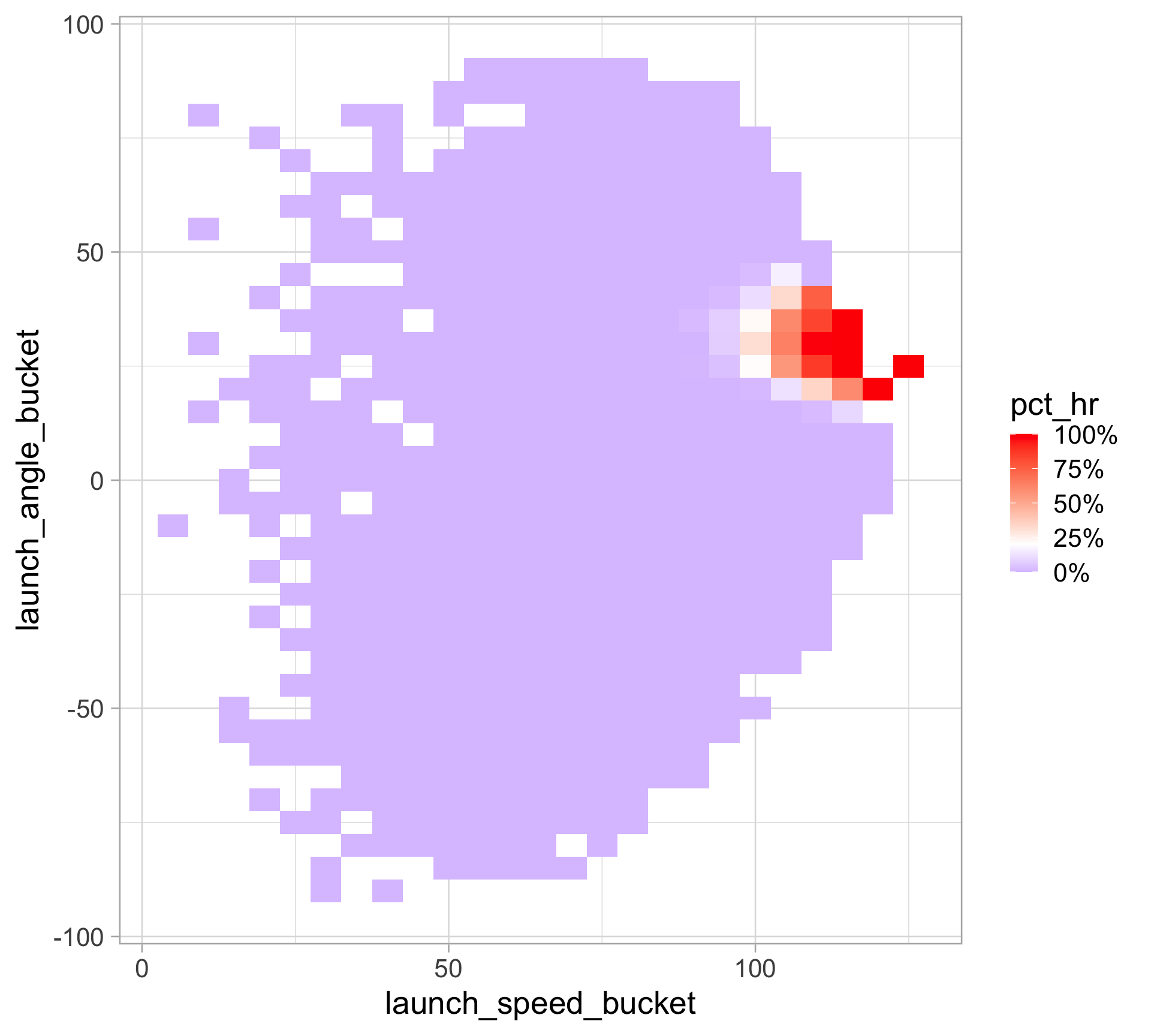

Predicting HRs with launch angle and exit velocity

HRs are relatively rare and confined to one area of this plot

Predicting HRs with launch angle and exit velocity

There is a sweet spot of launch_angle (mid-way ish) and launch_speed (relatively high) where almost all HRs occur

batted_balls |>

group_by(

launch_angle_bucket = round(launch_angle * 2, -1) / 2,

launch_speed_bucket = round(launch_speed * 2, -1) / 2

) |>

summarize(hr = sum(is_hr == 1),

n = n()) |>

ungroup() |>

mutate(pct_hr = hr / n) |>

ggplot(aes(x = launch_speed_bucket,

y = launch_angle_bucket,

fill = pct_hr)) +

geom_tile() +

scale_fill_gradient2(labels = scales::percent_format(),

low = "blue",

high = "red",

midpoint = 0.2)

Fitting GAMs with mgcv

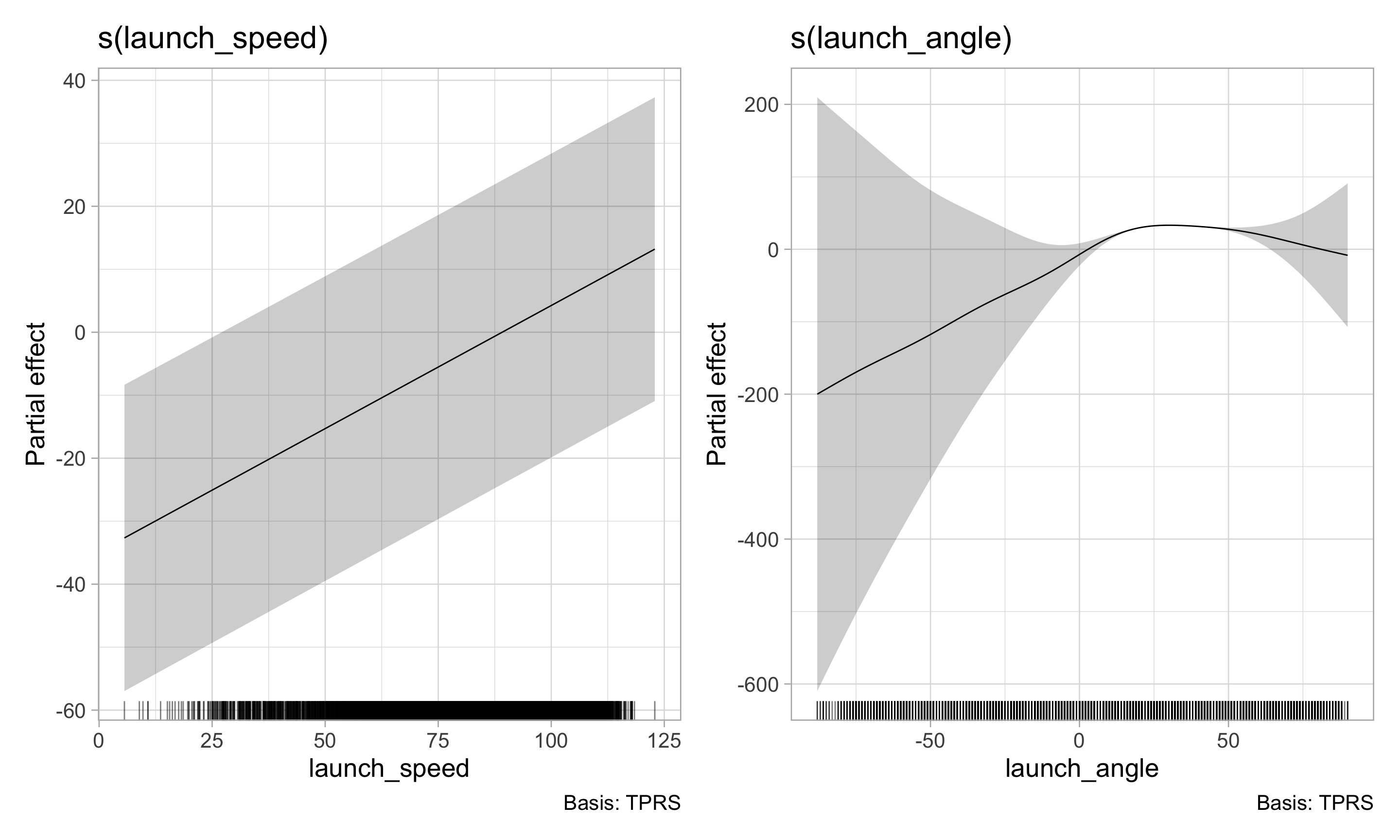

- Modeling the log-odds of a home run using non-linear functions of

launch_speedandlaunch_angle\[ \log \left( \frac{p_{\texttt{is_hr}}}{1 - p_\texttt{is_hr}} \right) = \beta_0 + s_1 (\texttt{launch_speed}) + s_2 (\texttt{launch_angle})\] where \(p_\texttt{is_hr}\) is the probability of a home run

View model summary

mgcvperforms hypothesis tests for the smooth terms — these are roughly the equivalent of an \(F\)-test for dropping each termEffective degrees of freedom (edf): basically the number of free parameters required to represent the function

In a smoothing spline, different choices of \(\lambda\) correspond to different values of the edf, representing different amounts of smoothness

# A tibble: 2 × 5

term edf ref.df statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 s(launch_speed) 1.00 1.00 804. 0

2 s(launch_angle) 3.73 3.98 468. 0# A tibble: 1 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -38.3 12.3 -3.11 0.00189Visualize partial response functions

Display the partial effect of each term in the model and how they add up to the overall prediction

Model comparison: GAM vs GLM (logistic regression)

- 10-fold cross-validation: assigning games to folds

Cross-validation

hr_cv <- function(x) {

hr_train <- batted_balls |> filter(fold != x)

hr_test <- batted_balls |> filter(fold == x)

gam_fit <- gam(is_hr ~ s(launch_speed) + s(launch_angle),

family = binomial,

method = "REML",

data = hr_train)

logit_fit <- glm(is_hr ~ launch_speed + launch_angle,

family = binomial, data = hr_train)

hr_out <- tibble(

gam_pred = predict(gam_fit, newdata = hr_test, type = "response"),

logit_pred = predict(logit_fit, newdata = hr_test, type = "response"),

test_actual = hr_test$is_hr,

test_fold = x

)

return(hr_out)

}

hr_preds <- map(1:N_FOLDS, hr_cv) |>

list_rbind()Out-of-sample comparison

Very few situations in reality where GLMs (with a linear predictor) perform better than an additive model using smooth functions

Especially since smooth functions can just capture linear models

hr_preds |>

pivot_longer(cols = gam_pred:logit_pred,

names_to = "model",

values_to = "test_pred") |>

mutate(test_pred_class = round(test_pred)) |>

group_by(model, test_fold) |>

summarize(accuracy = mean(test_pred_class == test_actual)) |>

group_by(model) |>

summarize(cv_accuracy = mean(accuracy),

se_accuracy = sd(accuracy) / sqrt(N_FOLDS))# A tibble: 2 × 3

model cv_accuracy se_accuracy

<chr> <dbl> <dbl>

1 gam_pred 0.973 0.00105

2 logit_pred 0.959 0.00148