Supervised learning: the tradeoffs

SURE 2024

Department of Statistics & Data Science

Carnegie Mellon University

Background

Concepts that hopefully you’ll be able to distinguish

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

- Classification vs. regression

- Classification vs. clustering

- Explanatory vs. response variable

- Inference vs. prediction

- Flexibility-interpretability tradeoff

- Bias-variance tradeoff

- Model assessment vs. model selection

- Parametric vs. nonparametric models

Statistical learning

Statistical learning refers to a set of tools for making sense of complex datasets. — Preface of ISLR

General setup: Given a dataset of \(p\) variables (columns) and \(n\) observations (rows) \(x_1,\dots,x_n\).

For observation \(i\), \[x_{i1},x_{i2},\ldots,x_{ip} \sim P \,,\] where \(P\) is a \(p\)-dimensional distribution that we might not know much about a priori

Supervised learning

Response variable \(Y\) in one of the \(p\) variables (columns)

The remaining \(p-1\) variables are predictor measurements \(X\)

Regression: \(Y\) is quantitative

Classification: \(Y\) is categorical

Goal: uncover associations between a set of predictor (independent / explanatory) variables / features and a single response (or dependent) variable

Accurately predict unseen test cases

Understand which features affect the response (and how)

Assess the quality of our predictions and inferences

They’re all the same

Supervised learning

Examples

- Identify the risk factors for prostate cancer

- Predict whether someone will have a heart attack based on demographic, diet, and clinical measurements

- Predict a player’s batting average in year \(t+1\) using their batting average in year \(t\) and uncover meaningful relationships between other measurements and batting average in year \(t+1\)

- Given NFL player tracking data which contain 2D coordinates of every player on the field at every tenth of the second, predict how far a ball-carrier will go at any given moment within a play

Examples of statistical learning methods / algorithms

You are probably already familiar with statistical learning - even if you did not know what the phrase meant before

Examples of statistical learning algorithms include:

Generalized linear models (GLMs) and penalized versions (lasso, ridge, elastic net)

Smoothing splines, generalized additive models (GAMs)

Decision trees and its variants (e.g., random forests, boosting)

Neural networks

Two main types of problems

Regression models: estimate average value of response (i.e. the response is quantitative)

Classification models: determine the most likely class of a set of discrete response variable classes (i.e. the response is categorical)

Which method should I use in my analysis?

IT DEPENDS - the big picture: inference vs prediction

Let \(Y\) be the response variable, and \(X\) be the predictors, then the learned model will take the form:

\[ \hat{Y}=\hat{f}(X) \]

Care about the details of \(\hat{f}(X)\)? \(\longrightarrow\) inference

Fine with treating \(\hat{f}(X)\) as a obscure/mystical machine? \(\longrightarrow\) prediction

Any algorithm can be used for prediction, however options are limited for inference

Active area of research on using more mystical models for statistical inference

The tradeoffs

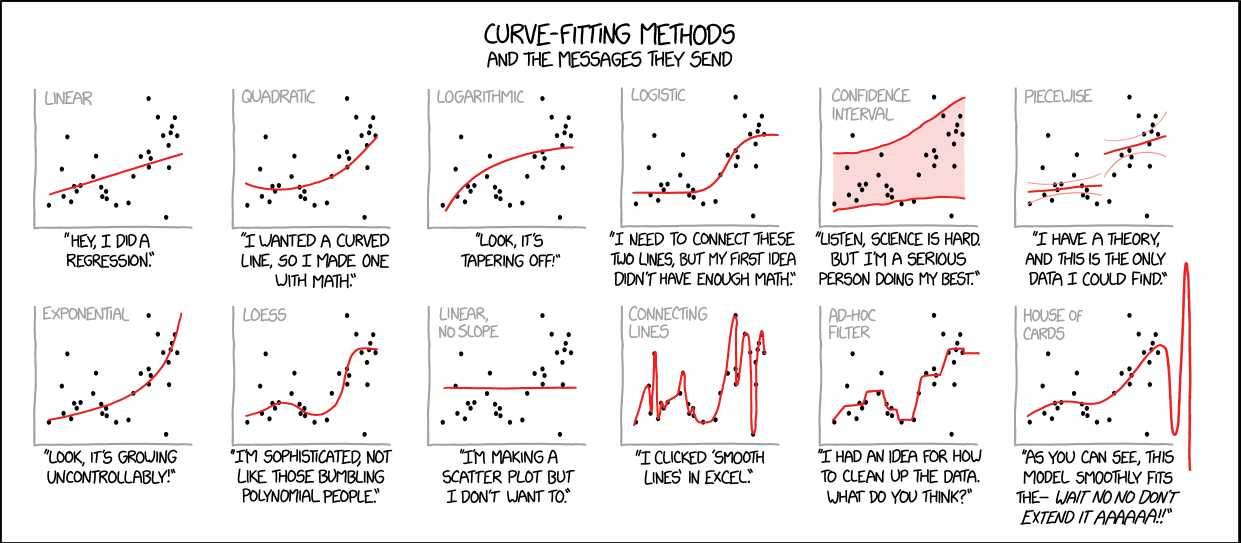

Some tradeoffs

Prediction accuracy vs interpretability

- Linear models are easy to interpret; boosted trees are not

Good fit vs overfit or underfit

- How do we know when the fit is just right?

Parsimony versus black-box

- We often prefer a simpler model involving fewer variables over a black-box involving more (or all) predictors

Model flexibility vs interpretability

Generally speaking: tradeoff between a model’s flexibility (i.e. how “wiggly” it is) and how interpretable it is

The simpler parametric form of the model, the easier it is to interpret

Hence why linear regression is popular in practice

Model flexibility vs interpretability

- Parametric models, for which we can write down a mathematical expression for \(f(X)\) before observing the data, a priori (e.g. linear regression), are inherently less flexible

- Nonparametric models, in which \(f(X)\) is estimated from the data (e.g. kernel regression)

Model flexibility vs interpretability

If your goal is prediction, your model can be as arbitrarily flexible as it needs to be

We’ll discuss how to estimate the optimal amount of flexibility shortly…

Looks about right…

Model assessment vs selection, what’s the difference?

Model assessment:

- evaluating how well a learned model performs, via the use of a single-number metric

Model selection:

- selecting the best model from a suite of learned models (e.g., linear regression, random forest, etc.)

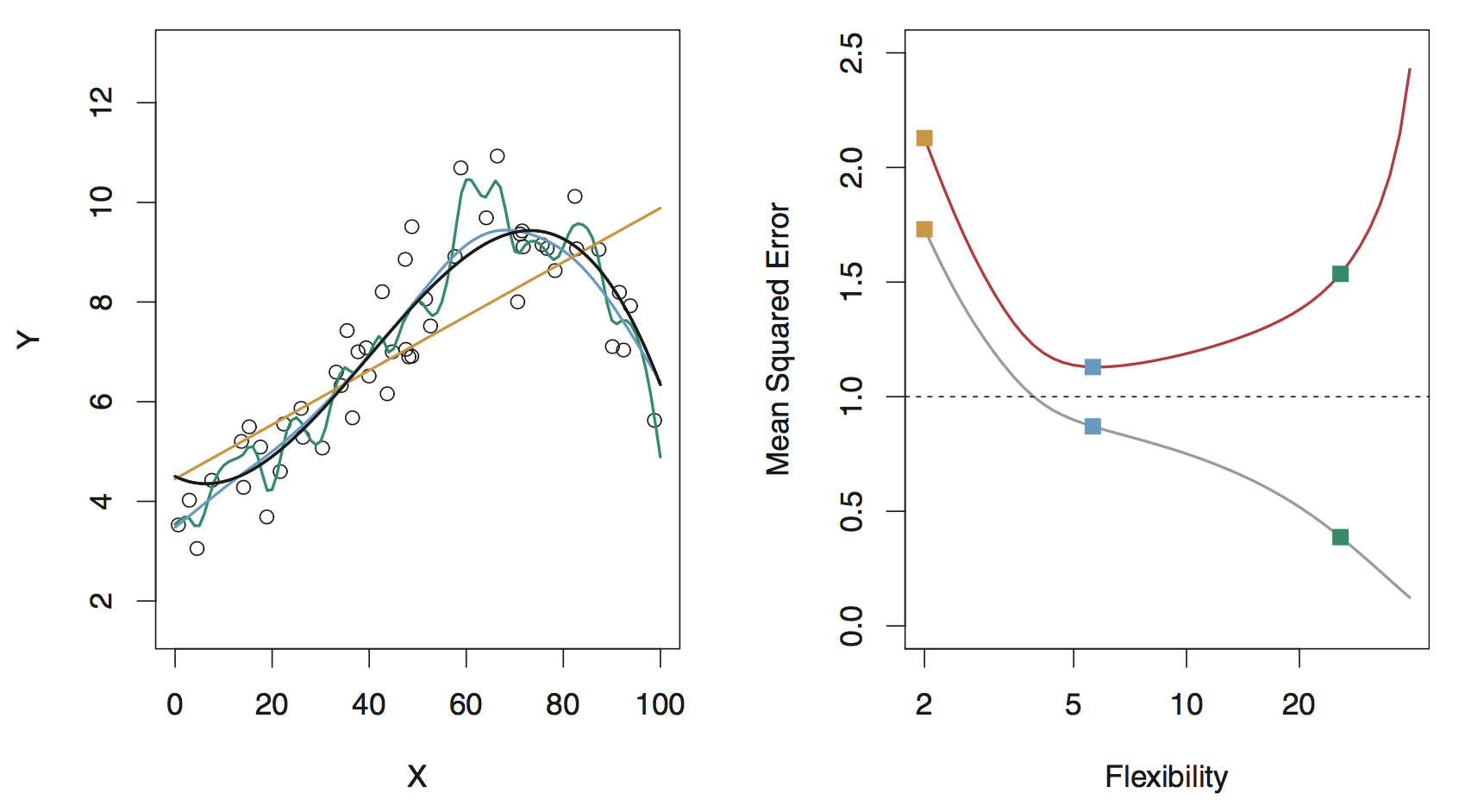

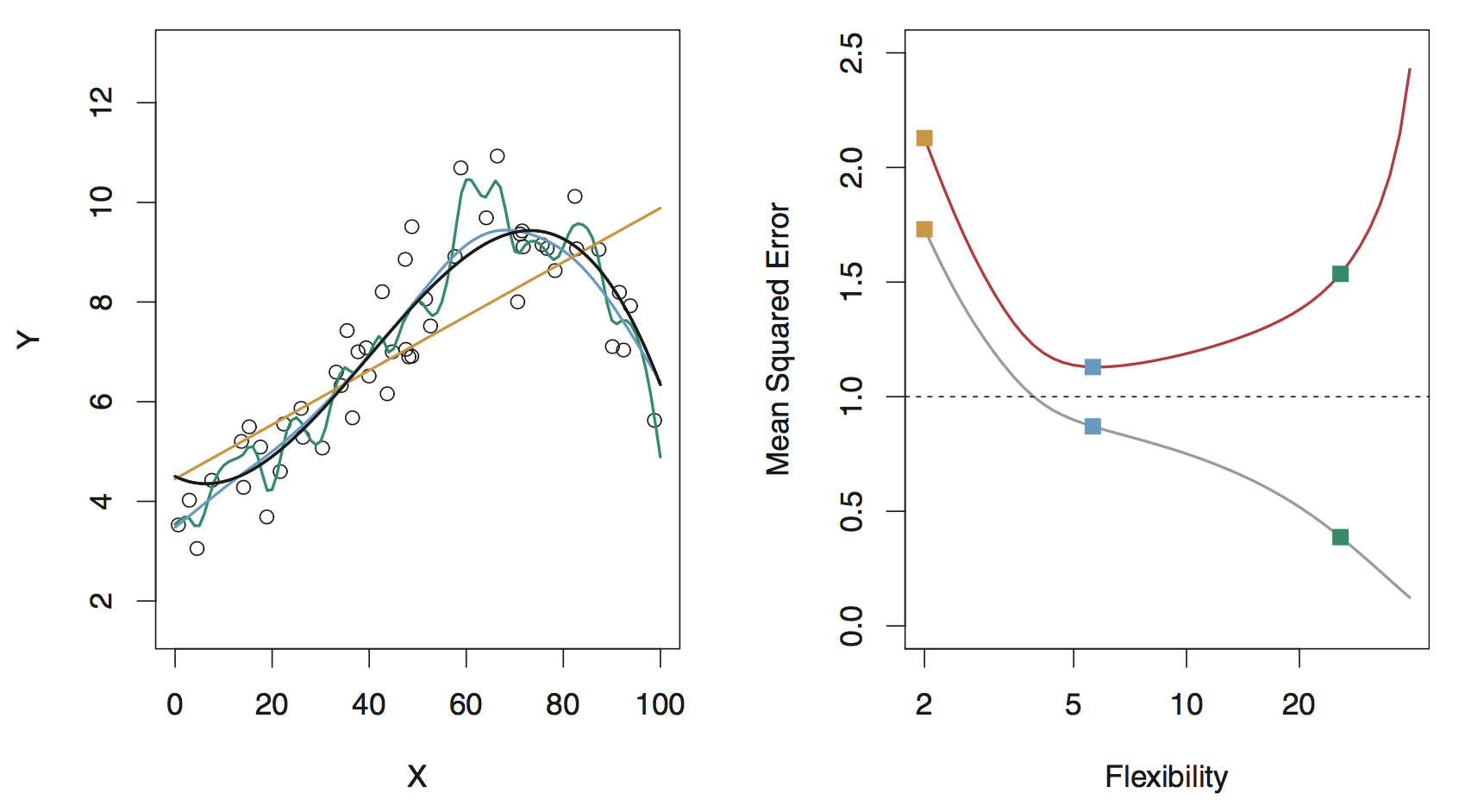

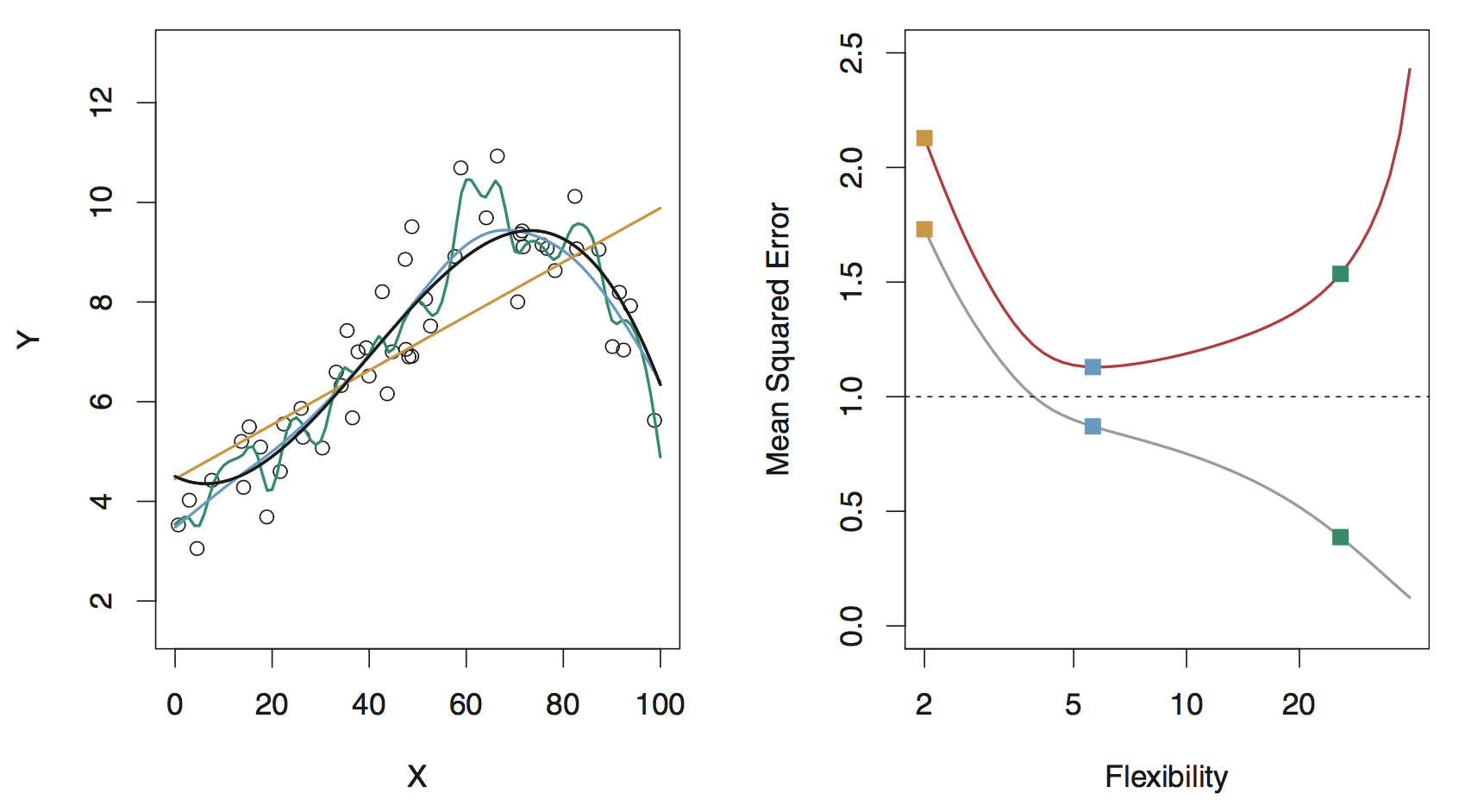

Model flexibility (ISLR Figure 2.9)

Left panel: intuitive notion of the meaning of model flexibility

Data are generated from a smoothly varying non-linear model (shown in black), with random noise added: \[ Y = f(X) + \epsilon \]

Model flexibility

Orange line: an inflexible, fully parametrized model (simple linear regression)

- Cannot provide a good estimate of \(f(X)\)

- Cannot overfit by modeling the noisy deviations of the data from \(f(X)\)

Model flexibility

Green line: an overly flexible, nonparametric model

- It can provide a good estimate of \(f(X)\)

- … BUT it goes too far and overfits by modeling the noise

This is NOT generalizable: bad job of predicting response given new data NOT used in learning the model

So… how do we deal with flexibility?

GOAL: We want to learn a statistical model that provides a good estimate of \(f(X)\) without overfitting

There are two common approaches:

We can split the data into two groups:

training data: data used to train models,

test data: data used to test them

By assessing models using “held-out” test set data, we act to ensure that we get a generalizable(!) estimate of \(f(X)\)

We can repeat data splitting \(k\) times:

Each observation is placed in the “held-out” / test data exactly once

This is called k-fold cross validation (typically set \(k\) to 5 or 10)

\(k\)-fold cross validation is the preferred approach, but the tradeoff is that CV analyses take \({\sim}k\) times longer than analyses that utilize data splitting

Model assessment

- Right panel shows a metric of model assessment, the mean squared error (MSE) as a function of flexibility for both a training and test datasets

- Training error (gray line) decreases as flexibility increases

- Test error (red line) decreases while flexibility increases until the point a good estimate of \(f(X)\) is reached, and then it increases as it overfits to the training data

Model assessment metrics

Loss function (aka objective or cost function) is a metric that represents the quality of fit of a model

For regression we typically use mean squared error (MSE) - quadratic loss: squared differences between model predictions \(\hat{f}(X)\) and observed data \(Y\)

\[\text{MSE} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_i^n (Y_i - \hat{f}(X_i))^2\]

For classification, the situation is not quite so clear-cut

misclassification rate: percentage of predictions that are wrong

area under the ROC curve (AUC)

interpretation can be affected by class imbalance:

if two classes are equally represented in a dataset, a misclassification rate of 2% is good

but if one class comprises 99% of the data, that 2% is no longer such a good result…

Back to model selection

Model selection: picking the best model from a suite of possible models

- Example: Picking the best regression model based on MSE, or best classification model based on misclassification rate

Two things to keep in mind:

- Ensure an apples-to-apples comparison of metrics

every model should be learned using the same training and test data

Do not resample the data between the time when you, e.g., perform linear regression and vs you perform random forest

- An assessment metric is a random variable, i.e., if you choose different data to be in your training set, the metric will be different.

For regression, a third point should be kept in mind: a metric like the MSE is unit-dependent

- an MSE of 0.001 in one analysis context is not necessarily better or worse than an MSE of 100 in another context

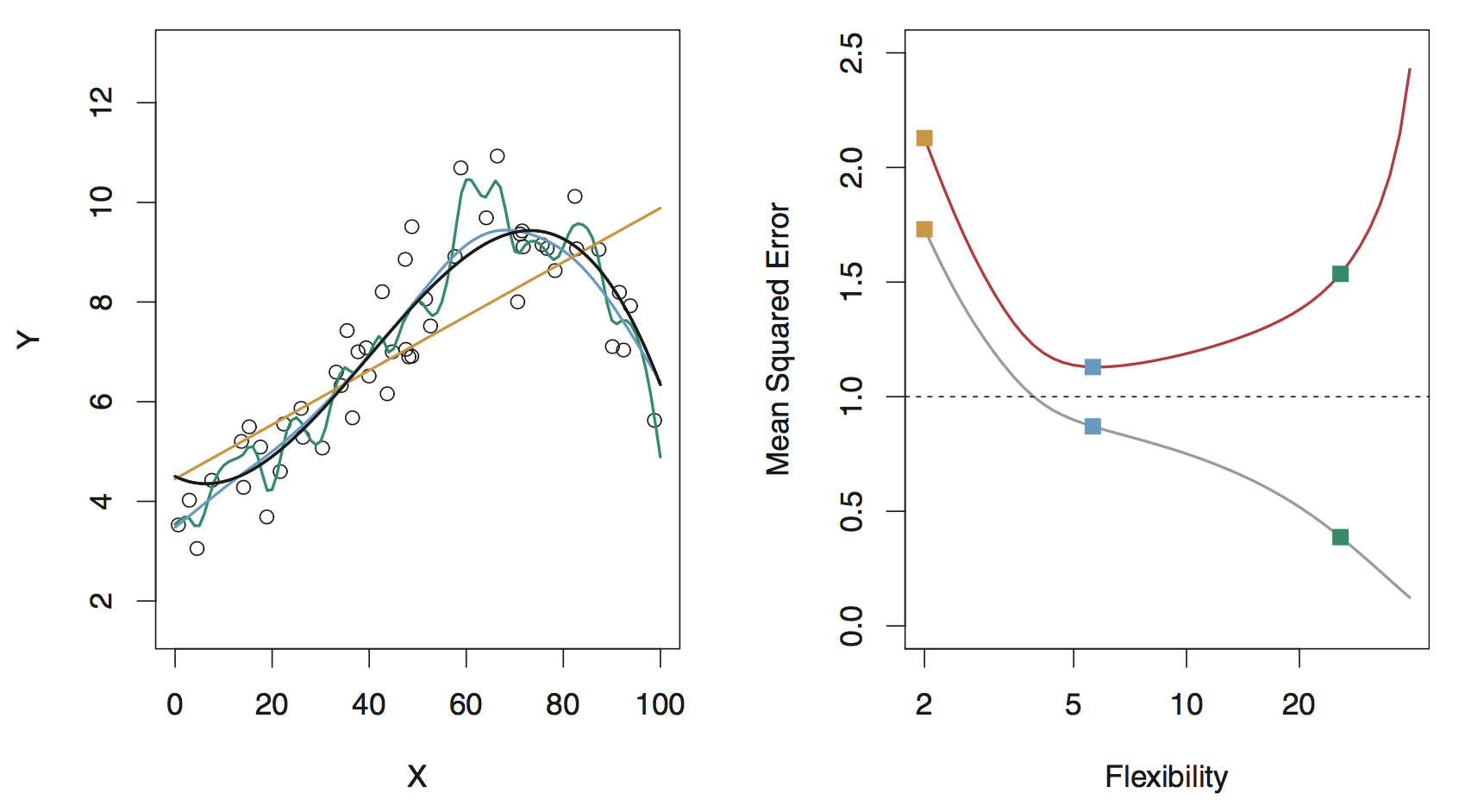

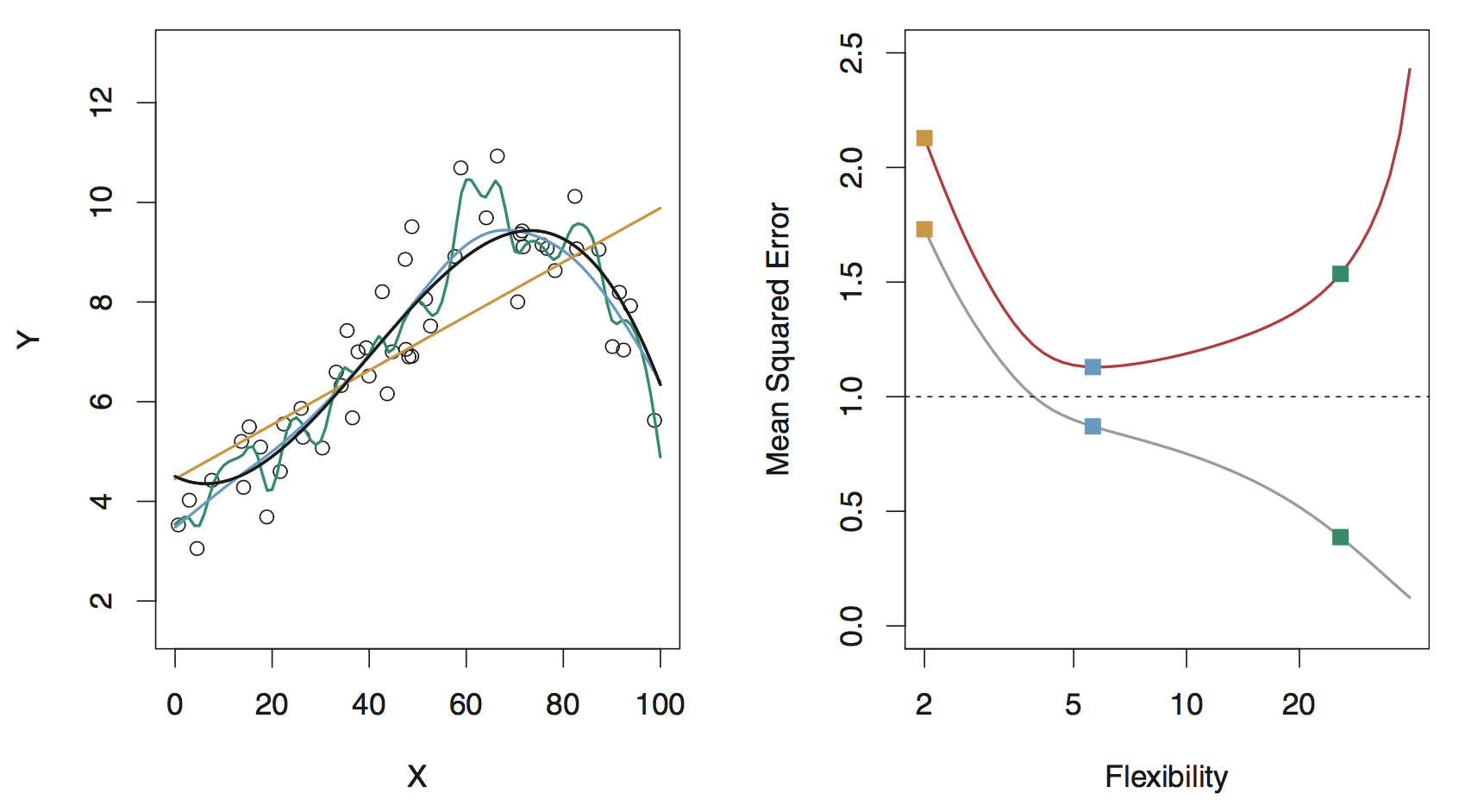

An example true model

The repeated experiments…

The linear regression fits

Look at the plots. For any given value of \(x\):

- The average estimated \(y\) value is offset from the truth (high bias)

- The dispersion (variance) in the estimated \(y\) values is relatively small (low variance)

The spline fits

Look at the plots. For any given value of \(x\):

- The average estimated \(y\) value approximately matches the truth (low bias)

- The dispersion (variance) in the estimated \(y\) values is relatively large (high variance)

Bias-variance tradeoff

“Best” model minimizes the test-set MSE, where the true MSE can be decomposed into \({\rm MSE} = {\rm (Bias)}^2 + {\rm Variance}\)

Towards the left: high bias, low variance. Towards the right: low bias, high variance.

Optimal amount of flexibility lies somewhere in the middle (“just the right amount” — Goldilocks principle)

“The sweet spot”

Remember, when building predictive models, try to find the sweet spot between bias and variance. #babybear

— Dr. G. J. Matthews (@StatsClass) September 6, 2018

Principle of parsimony (Occam’s razor)

“Numquam ponenda est pluralitas sine necessitate” (plurality must never be posited without necessity)

From ISLR:

When faced with new data modeling and prediction problems, it’s tempting to always go for the trendy new methods. Often they give extremely impressive results, especially when the datasets are very large and can support the fitting of high-dimensional nonlinear models. However, if we can produce models with the simpler tools that perform as well, they are likely to be easier to fit and understand, and potentially less fragile than the more complex approaches. Wherever possible, it makes sense to try the simpler models as well, and then make a choice based on the performance/complexity tradeoff.

In short: “When faced with several methods that give roughly equivalent performance, pick the simplest.”

The curse of dimensionality

The more features, the merrier?… Not quite

Adding additional signal features that are truly associated with the response will improve the ftted model

- Reduction in test set error

Adding noise features that are not truly associated with the response will lead to a deterioration in the model

- Increase in test set error

Noise features increase the dimensionality of the problem, increasing the risk of overfitting