library(tidyverse)

theme_set(theme_light())

pima <- as_tibble(MASS::Pima.tr)

pima <- pima |>

mutate(pregnancy = ifelse(npreg > 0, "Yes", "No")) # whether the patient has had any pregnanciesSupervised learning: logistic regression

SURE 2024

Department of Statistics & Data Science

Carnegie Mellon University

Background

Classification

Categorical variables take values in an unordered set with different categories

Classification: predicting a categorical response \(Y\) for an observation (since it involves assigning the observation to a category/class)

Often, we are more interested in estimating the probability for each category of the response \(Y\)

Classification is different from clustering, since we know the true label \(Y\)

We will focus on binary categorical response (categorical response variables with only two categories)

- Examples: whether it will rain or not tomorrow, whether the kicker makes or misses a field goal attempt

Logistic regression

Review: in linear regression, the response variable \(Y\) is continuous

Logistic regression is used to model binary outcomes (i.e. \(Y \in \{0, 1\}\))

Similar concepts from linear regression

- tests for coefficients

- indicator variables

- model selection techniques

- regularization

Other concepts are different

- interpretation of coefficients

- residuals are not normally distributed

- model evaluation

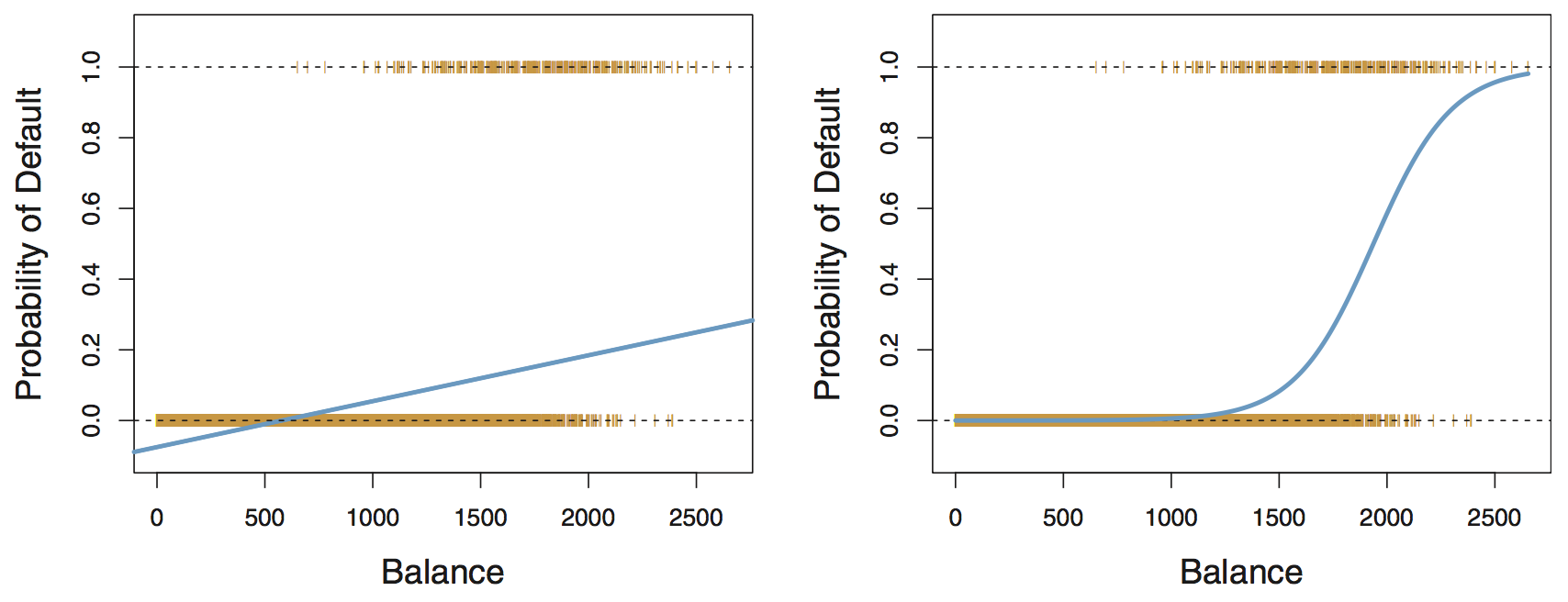

Why not linear regression for categorical data?

From ISLR:

Linear regression

predicted probabilities might be outside the \([0, 1]\) interval

Logistic regression

all probabilities lie between 0 and 1

Logistic regression

Logistic regression models the probability of success \(p(x)\) of a binary response variable \(Y \in \{0, 1\}\)

To limit the regression between \([0, 1]\), we use the logit function, or the log-odds ratio

\[ \log \left( \frac{p(x)}{1 - p(x)} \right) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \cdots + \beta_p x_p \]

or equivalently,

\[ p(x) = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \cdots + \beta_p x_p}}{1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \cdots + \beta_p x_p}} \]

- Note: \(p(x)= P(Y = 1 \mid X = x) = \mathbb E[Y \mid X = x]\)

Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE)

- Likelihood function: how likely to observe data for given parameter values \[L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^n f(y_i; \theta)\]

- Goal: find values for parameters that maximize likelihood function (i.e., MLEs)

- Why: likelihood methods can handle variety of data types and assumptions

How: typically numerical approaches and optimization techniques

- Easier to work with log-likelihood (sums compared to products)

Example: linear regression MLE

Reminder: probability density function (pdf) for a normal distribution \[f(y \mid \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} e^{\frac{-(y - \mu) ^ 2}{2 \sigma^2}}\]

Consider a simple linear regression model (with an intercept and one predictor) \[y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_i + \epsilon_i, \quad \epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\]

Then \(\qquad \displaystyle L(\beta_0, \beta_1, \sigma) = \prod_{i=1}^n f(y_i \mid x_i; \beta_0, \beta_1, \sigma) = \prod_{i=1}^n \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma^2}} e^{\frac{-(y_i - \beta_0 - \beta_1 x_i) ^ 2}{2 \sigma^2}}\)

And \(\qquad \displaystyle \log L(\beta_0, \beta_1, \sigma) = -\frac{n}{2} \log 2\pi - \frac{n}{2} \log \sigma^2 - \frac{1}{2 \sigma^2} \sum_{i=1}^n (y_i - \beta_0 - \beta_1x_1)^2\)

We can then use calculus to find the optimal parameter values. For more details, see here

Major difference between linear and logistic regression

Logistic regression involves numerical optimization

- \(y_i\) is observed response for \(n\) observations, either 0 or 1

- We need to use an iterative algorithm to find \(\beta\)’s that maximize the likelihood \[\prod_{i=1}^{n} p\left(x_{i}\right)^{y_{i}}\left(1-p\left(x_{i}\right)\right)^{1-y_{i}}\]

- Newton’s method: start with initial guess, calculate gradient of log-likelihood, add amount proportional to the gradient to parameters, moving up log-likelihood surface

- This means logistic regression runs more slowly than linear regression

- if you’re interested: iteratively re-weighted least squares, see here

Inference with logistic regression

Major motivation for logistic regression (and all GLMs) is inference

- How does the response change when we change a predictor by one unit?

- For linear regression, the answer is straightforward

\[\mathbb{E}[Y \mid x] = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + + \cdots + \beta_p x_p\]

- For logistic regression, it is a little less straightforward

\[\mathbb E[Y \mid x] = \frac{e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \cdots + \beta_p x_p}}{1 + e^{\beta_0 + \beta_1 x_1 + \cdots + \beta_p x_p}}\]

Note:

The predicted response varies non-linearly with the predictor variable values

Interpretation on the odds scale

The odds interpretation

The odds of an event are the probability of the event divided by the probability of the event not occurring

\(\displaystyle \text{odds} = \frac{\text{probability}}{1 - \text{probability}}\)

\(\displaystyle \text{probability} = \frac{\text{odds}}{1 + \text{odds}}\)

Example: Rolling a fair six-sided die

The probability of rolling a 2 is 1/6

The odds of rolling a 2 is 1 to 5 (or 1:5)

The odds interpretation

Suppose we fit a simple logistic regression model (with one predictor), and say the predicted probability is 0.8 for a particular predictor value

This means that if we were to repeatedly sample response values given that predictor variable value: we expect class 1 to appear 4 times as often as class 0 \[\text{odds} = \frac{\mathbb{E}[Y \mid x]}{1-\mathbb{E}[Y \mid x]} = \frac{0.8}{1-0.8} = 4 = e^{\beta_0+\beta_1x}\]

Thus we say that for the given predictor variable value, the odds are 4 (or 4:1) in favor of class 1

How does the odds change if we change the value of a predictor variable by one unit?

\[\text{odds}_{\rm new} = e^{\beta_0+\beta_1(x+1)} = e^{\beta_0+\beta_1x}e^{\beta_1} = e^{\beta_1}\text{odds}_{\rm old}\]

For every unit change in \(x\), the odds change by a factor \(e^{\beta_1}\)

Example

Data: diabetes in the Pima

Each observation represents one Pima woman, at least 21 years old, who was tested for diabetes as part of the study.

type: if they had diabetes according to the diagnostic criterianpreg: number of pregnanciesbp: blood pressure

Fitting a logistic regression model

- Use the

glmfunction, but specify the family isbinomial - Get coefficients table using the

tidy()function in thebroompackage

pima_logit <- glm(type ~ pregnancy + bp, data = pima, family = binomial)

library(broom)

# summary(pima_logit)

tidy(pima_logit)# A tibble: 3 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -3.16 1.08 -2.94 0.00329

2 pregnancyYes -0.468 0.427 -1.10 0.273

3 bp 0.0403 0.0140 2.89 0.00391- Eponentiate the coefficient estimates (log-odds) to back-transform and get the odds

# A tibble: 3 × 7

term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) 0.0422 1.08 -2.94 0.00329 0.00472 0.329

2 pregnancyYes 0.626 0.427 -1.10 0.273 0.272 1.47

3 bp 1.04 0.0140 2.89 0.00391 1.01 1.07 Interpreting a logistic regression model

# A tibble: 3 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -3.16 1.08 -2.94 0.00329

2 pregnancyYes -0.468 0.427 -1.10 0.273

3 bp 0.0403 0.0140 2.89 0.00391- Intercept: the estimated log-odds of diabetes for a Pima woman who has never been pregnant and has a diastolic blood pressure of 0 (hmm…) are -3.16, so the odds are exp(-3.16) = 0.0422

Interpreting a logistic regression model

# A tibble: 3 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -3.16 1.08 -2.94 0.00329

2 pregnancyYes -0.468 0.427 -1.10 0.273

3 bp 0.0403 0.0140 2.89 0.00391- Pregnancy: pregnancy changes the log-odds of diabetes, relative to the baseline value, by -0.468. The odds ratio is exp(-0.47) = 0.626

Interpreting a logistic regression model

# A tibble: 3 × 5

term estimate std.error statistic p.value

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 (Intercept) -3.16 1.08 -2.94 0.00329

2 pregnancyYes -0.468 0.427 -1.10 0.273

3 bp 0.0403 0.0140 2.89 0.00391Blood pressure: each unit of increase in blood pressure (in mmHg) is associated with an increase in the log-odds of diabetes of 0.0403, or an increase in the odds of diabetes by a multiplicative factor of exp(0.0403) = 1.04

- Every extra mmHg in blood pressure multiplies the odds of diabetes by 1.04

View predicted probability relationship

Effects plot

Nonlinear relationship between blood pressure and probability of diabetes

The gap between women who were or were not previously pregnant is different across the range

Deviance

For model of interest \(\mathcal{M}\) the total deviance is

\[D_{\mathcal{M}}= -2 \log \frac{\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{M}}}{\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{S}}} = 2\left(\log \mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{S}}-\log \mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{M}}\right)\]

- \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{M}}\) is the likelihood for model \(\mathcal{M}\)

\(\mathcal{L}_{\mathcal{S}}\) is the likelihood for the saturated model, with \(n\) parameters

- i.e. the most complex model possible, with separate parameter for each observation and provides a perfect fit to the data

Deviance is a measure of goodness-of-fit: the smaller the deviance, the better the fit

- Generalization of RSS in linear regression to any distribution family

For more, see here

Deviance residuals

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

-1.5293 -0.9156 -0.7463 -0.0990 1.3205 1.9326 Remember Pearson residual?

A deviance residual is an alternative residual for logistic regression based on the discrepancy between the observed values and those estimated using the likelihood \[d_i = \mbox{sign}(y_i-\hat{p}_i) \sqrt{-2[y_i \log \hat{p}_i + (1-y_i) \log (1 - \hat{p}_i)]}\] where \(y_i\) is the \(i\)-th observed response and \(\hat p_i\) is the estimated probability of success

Note: The use of the sign of the difference ensures that the deviance residuals are positive/negative when the observation is larger/smaller than predicted.

- The sum of the individual deviance residuals is the total deviance

Model measures

# A tibble: 1 × 8

null.deviance df.null logLik AIC BIC deviance df.residual nobs

<dbl> <int> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <int> <int>

1 256. 199 -123. 252. 262. 246. 197 200deviance=2 * logLiknull.deviancecorresponds to intercept-only modelAIC=2 * df.residual - 2 * logLikWe will consider these to be less important than out-of-sample/test set performances

Predictions

The default output of

predict()is on the log-odds scaleTo get predicted probabilities, specify

type = "response

How do we predict the class (diabetes or not)?

Typically if predicted probability is > 0.5 then we predict

Yes, elseNo- Could also be encoded as

1and0

- Could also be encoded as

Model assessment

- Confusion matrix

Observed

Predicted No Yes

No 125 60

Yes 7 8Calibration

If we have a model that tells us the probability of rain in a given time period (i.e. a week) is 50%, it had better rain on half of the days, or the model is just wrong about the probability of rain

A classifier is calibrated if in the given time period, the percentage of days it actually rained when the forecast predicted \(x \%\) percent chance of rain is \(x \%\)

In short, for a model to be calibrated, the actual probabilities should match the predicted probabilities

- Calibration should be used together with other model evaluation and diagnostic tools

- A model is well-calibrated does not mean it is good at making predictions (example: a constant classifier)

See also: Hosmer-Lemeshow test

Calibration plot: smoothing

Plot the observed outcome against the fitted probability, and apply a smoother

Looks good for the most part

odd behavior for high probability values

since there are only a few observations with high predicted probability

Calibration plot: binning

pima |>

mutate(

pred_prob = predict(pima_logit, type = "response"),

bin_pred_prob = cut(pred_prob, breaks = seq(0, 1, .1))

) |>

group_by(bin_pred_prob) |>

summarize(n = n(),

bin_actual_prob = mean(type == "Yes")) |>

mutate(mid_point = seq(0.15, 0.65, 0.1)) |>

ggplot(aes(x = mid_point, y = bin_actual_prob)) +

geom_point(aes(size = n)) +

geom_line() +

geom_abline(slope = 1, intercept = 0,

color = "black", linetype = "dashed") +

# expand_limits(x = c(0, 1), y = c(0, 1)) +

coord_fixed()

Other calibration methods

probablypackage in RFormally, a classifier is calibrated (or well-calibrated) when \(P(Y = 1 \mid\hat p(X) = p) = p\)